The Historic Mines of Custer County, Colorado |

||

Wayne I. Anderson |

||

Most of Colorado’s gold and silver mining districts line up in a northeast to southwest trend. Included in the trend are important mines near Gold Hill, Central City, Idaho Springs, Leadville, Telluride, Silverton, and La Plata. This zone, now called the Colorado Mineral Belt, is a zone of fracturing and intrusion of igneous rocks that formed when the Rocky Mountains were undergoing mountain building, some 75 million years ago to 40 million years ago. Not all of Colorado’s mineral wealth lies within the Colorado Mineral Belt, however. For example, the Cripple Creek District (the state’s largest gold-producing district) is located well to the east of the Colorado Mineral Belt. Ore deposits of the Cripple Creek area are about 10 million years younger than the ores of the Colorado Mineral Belt. Likewise, the historically-significant silver deposits of Custer County lie to the east of the Colorado Mineral Belt and are younger in age. The lush bottom lands of the Wet Mountain Valley in Custer County were settled by persons with farming and ranching interests. Later, significant mineral wealth was discovered in the neighboring hills of the Wet Mountains, or Sierra Mojada as they were once known. The grassy slopes and valleys of the Wet Mountains were favorite pasture lands for cattle of the local ranchers, and the first specimens of ore were picked up as curiosities by herdsmen who wandered over the hills in search of stray cattle. Some of these intriguing specimens were found to contain silver. In 1872, prospectors were attracted to the region in increased numbers. The first mine in the Wet Mountain Valley was developed in the autumn of 1872 in an outcrop of quartz that bore galena (lead sulfide) and silver glance (silver sulfide). The deposit was described as extremely rich. However, the ore pinched out below depths of 50 to 60 feet, and the mine was soon abandoned. |

|

|

||||

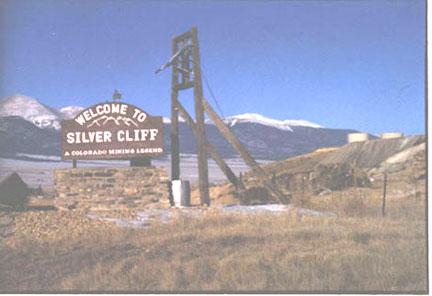

Silver Cliff, Rosita, Querida, and Bull Domingo all boasted productive mines in the late 1800s. |

||||

In 1874, a thin seam with copper carbonates and native silver was discovered near Rosita. Known as the Humboldt-Pocahontas vein, this occurrence became famous and produced the Humboldt, Pocahontas, Virginia, and East Leviathan claims. The Humboldt-Pocahontas Mine, developed in the ore body, proved to be a steady producer and was worked for nearly 15 years, yielding over $900,000 worth of ore. In short order, the hills around Rosita were honeycombed with prospector’s pits. At the height of its prosperity in the years 1875-1877, Rosita boasted a population of 1,200 to 1,500. Ores in the Rosita District are associated with Tertiary (approximately 26 to 32 million years old) volcanic activity that produced andesitic lavas, alternating with ash and fragmental material. Ore-bearing veins cut some of the volcanic rocks, indicating that emplacement of ore mineralization was late in the volcanic history of the region. In the Rosita area, mineralization is also common along faults which cut the Tertiary volcanic sequence. In 1877, an important mine opened about two miles north of Rosita. Known as the Bassick Mine in honor of its discoverer, E. G. Bassick, the mine proved to be quite rich. Ore worth $500,000 in gold and silver was taken from the mine during its first 18 months of operation, and the town of Querida sprang up around the mine. The ore body of the Bassick Mine outcrops on the flanks of Mount Tyndall. The ore occurs in a mass of brecciated (fragmented) volcanic rock, formed primarily of andesitic material. Cross, who published on the area in 1896, interpreted the brecciated rock as the filling of a volcanic neck. By 1878, the Rosita Hills had been thoroughly prospected and exploration shifted to the Silver Cliff Volcanic Center, near the present town of Silver Cliff. Three lumbermen, engaged in hauling timber from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to Rosita, noticed black-stained cliffs along the north side of what is today called Chloride Gulch. Later, they took time to examine the outcrops more closely and collected chunks of a dark, greasy-looking mineral. They discovered that the mineral melted to form silver, after heating in a stove. The three lumbermen (Edwards, Hafford, and Powell) had discovered the famous horn silver deposits of the Silver Cliff area. Another boom of mining activity resulted as the Racine Boy, Silver Cliff, and other claims were quickly developed. The bustling town of Silver Cliff grew rapidly, adjacent to the new mines and prospects. |

|

|

||

Dilapidated buildings at an old mine site in the White Hills, north of Silver Cliff, provide evidence of the area’s mining past. Sangre de Cristo Mountains are in the background. |

||

Mineralization in the Silver Cliff District is associated with Tertiary (approximately 26 to 32 million years old) volcanic rocks, primarily rhyolitic in composition. In addition, Tertiary volcanic glass, tuff (consolidated ash and other ejecta), and breccia are common. No well-defined ore body was found at the surface in the Silver Cliff area, but mineralization was associated with fractured rhyolite. Flakes of silver chloride (horn silver) were found in cracked-and-fissured rhyolite on the Silver Cliff and Racine Boy claims. The mineralized rocks and fractures were blackened with manganese oxide and iron oxide coatings, and it was the experience of early miners that silver did not occur outside the stained zones. In general, the early amalgamating mills were unsuccessful in treating the ores of the Silver Cliff District and a large portion of silver was carried away in the tailings. According to Emmons (1896), the Security-Geyser Mine was the only mine in the Silver Cliff District that extended, more than 100 feet in depth. It reached a depth of 2,100 feet, encountering Precambrian (1 to 2 billion years old) granite and gneiss at the 1,850 feet level. No well-defined ore body was found until the 1,850 feet level was reached. However, thin films and stains of metallic sulfides with high silver content were noted at scattered levels higher in the mine shaft. The main ore vein contained galena (lead sulfide), sphalerite (zinc sulfide), chalcopyrite (copper-iron sulfide), copper-bearing argentite (silver sulfide), tetrahedrite (copper-iron silver sulfide), and ruby silver (silver sulfide). |

|

|

||

Silver Cliff, once the third largest city in Colorado, was a major mining center in the late 1800s. Numerous prospector's pits and abandoned mines dot the modern landscape, reminding us of the area's past glory. |

||

The decade of the 1870s was the heyday for mining development in Custer County, and Rosita, Querida, and Silver Cliff trace their origins back to the 1870s. At about the same time, a remarkable discovery occurred in the nearby Blue Mountains (now called the Bull Domingo Hills). The discovery came to be known as the Bull-Domingo Mine, from the two claims that were consolidated to constitute the mining property. The Bull-Domingo Mine is located on the west flank of the Wet Mountain range. The area is underlain by ancient Precambrian (1 to 2 billion years old) gneiss, cut by dikes of granite, syenite, and diabase. The ore body is brecciated (fragmented) and may represent the filling of a volcanic neck or pipe. Ore occurs as coatings on boulders within the brecciated ore body. Mineralization includes galena (lead sulfide), sphalerite (zinc sulfide), and pyrite (iron sulfide). Silver occurred in the galena ore at about 68 ounces of silver per ton of galena. Between $500,000 and $1,000,000 worth of silver and lead were recovered from the Bull-Domingo Mine. Following the decade of the 1870s, the excitement of bountiful bodies of silver ore discovered at Leadville drew miners and prospectors from the Rosita area. This marked the beginning of the decline of the Rosita Mining District. At the same time, accounts of fabulous wealth acquired quickly through investments in Western mines were rampant in the East, where considerable capital was available for investing. In addition, many inexperienced individuals, looking to get rich quickly, came West to develop mines. Some of the surplus Eastern capital found its way to the Silver Cliff District. The Silver Cliff and the Bull-Domingo mines were sold to Eastern capitalists. Stocks of both mines were listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Apparently, no dividends were ever paid on the stock, even though each stock company was formed with an initial capital listing of $10,000,000. |

|

|

||

Round Mountain, a Tertiary volcano northeast of Silver Cliff, is pocked with prospect pits. |

||

According to Emmons (1896), it is not fair to ascribe the decline of the Custer County mines entirely to the nature and distribution of the ore bodies. Although the value of many of the mining properties were likely exaggerated during the mining boom of the 1870s, some of the ore bodies that were worked systematically and persistently proved to be profitable. Although records are incomplete, Emmons notes that the value of silver and gold produced in Custer County from 1880-1894 totaled $5,877,952. Most, if not all, of the gold production came from the Bassick Mine near Querida. Emmons (1896) reports that the Pioneer Mine at Rosita was credited with gold production in the late 1880s, but that the accuracy of the report is in doubt. In addition to silver, the Bull-Domingo Mine produced lead, as did the Terrible Mine on Oak Creek at Isle. Many of the mining failures can probably be blamed on the lack of experience of mine owners with proven mining techniques and smelting practices. They often disregarded fundamental principles of chemistry and metallurgy during the processing and treatment of ore. The glory days for mining in the Wet Mountain Valley were over by the turn of the century, but some mining continued on an intermittent basis during the 1900s. George Colgate of Hillside recalls that a few small mines were in operation north of Silver Cliff, prior to World War II. He worked in some of these mines from 1939 to 1941. The mines produced primarily lead and zinc, along with some silver. These were small operations with a work force of two to eight men. Most of the ore was shipped to Leadville, Colorado or El Paso, Texas for processing. Colgate also worked at the Bull-Domingo Mine after World War II, before that operation closed because of flooding. According to Turk (1975), a few silver mines in Custer County reopened in the 1960s when silver prices increased dramatically. Bill Humble conducted small-scale operations on his claims in the historic Cloverdale Mining District west of Hillside until his death in 2002. |

|

References Cappa, Jim. 2003. “Geology of Gold Deposits in Colorado”. Rock Talk, Division of Minerals and Geology, Colorado Geological Survey, vol.6, no. 2, p. 4-8. Colgate, George. 2002. personal communication. Cross, C. W. 1896. Geology of Silver Cliff and the Rosita Hills. U. S. Geological Survey Annual Report 17, Part 2, p. 269-403. Dodds, Joanne West. 1992. Custer County: Rosita, Silver Cliff, and Westcliffe. Focal Plain Printing, 42 p. Emmons, S. F. 1896. The Mines of Custer County, Colorado. U. S. Geological Survey Annual Report 17, Part 2, p. 405-472. Turk, Gayle. 1975. Wet Mountain Valley. Little London Press, 60 p. |

|

|

|

|

||||