Palczewski Suffrage Postcard Archive

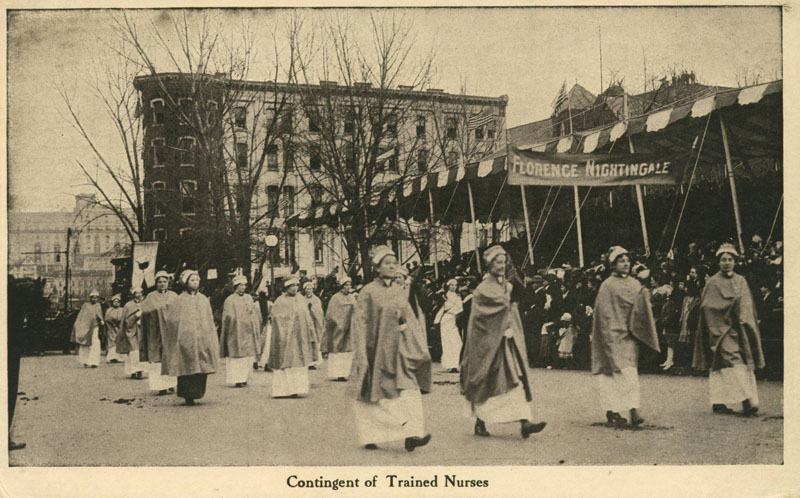

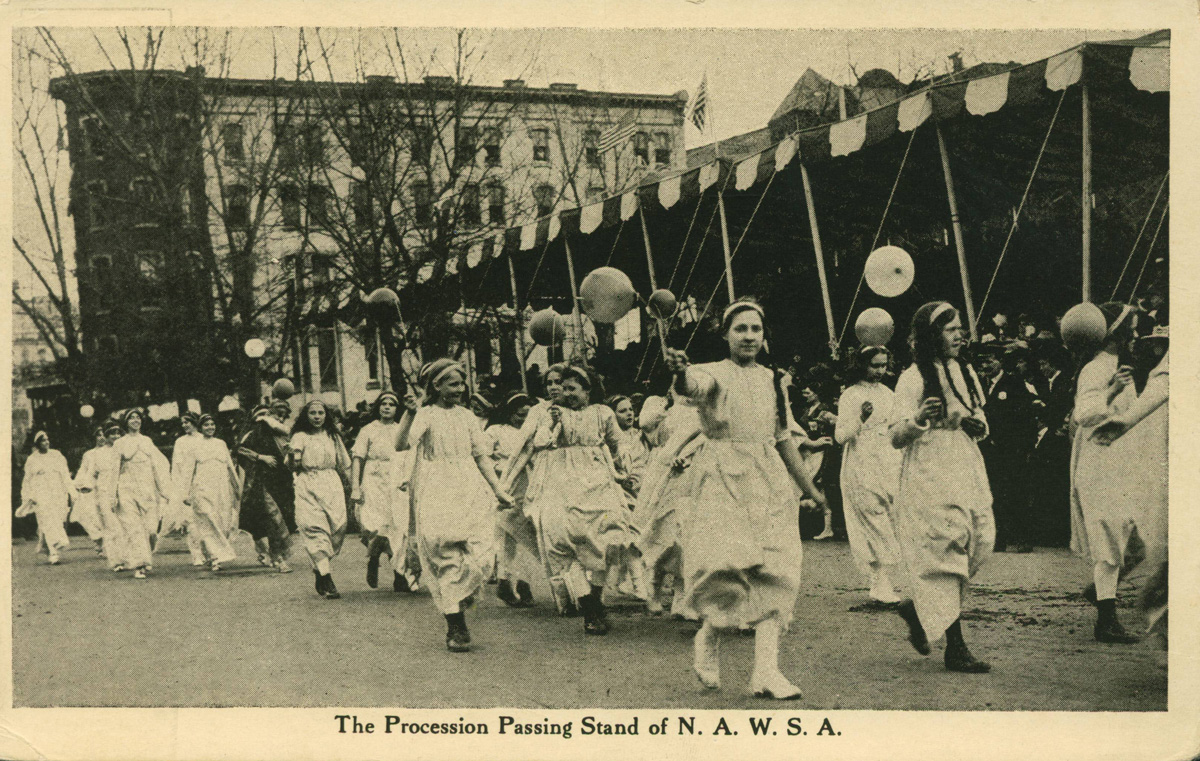

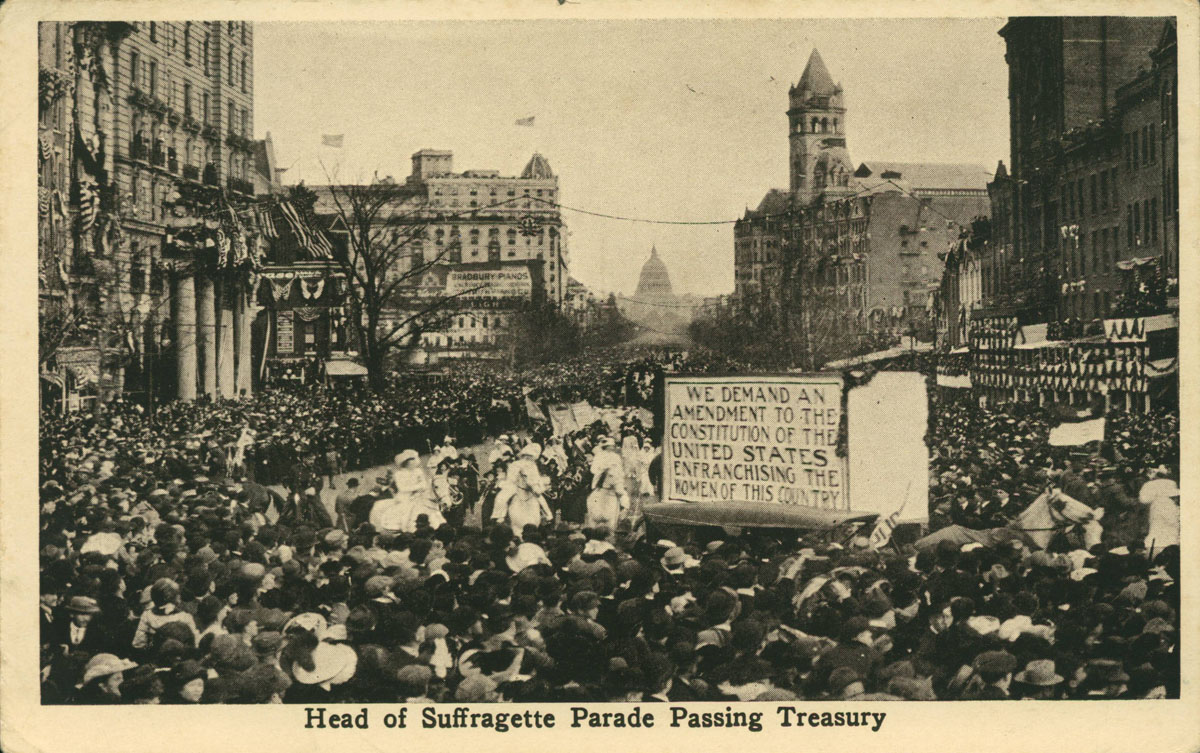

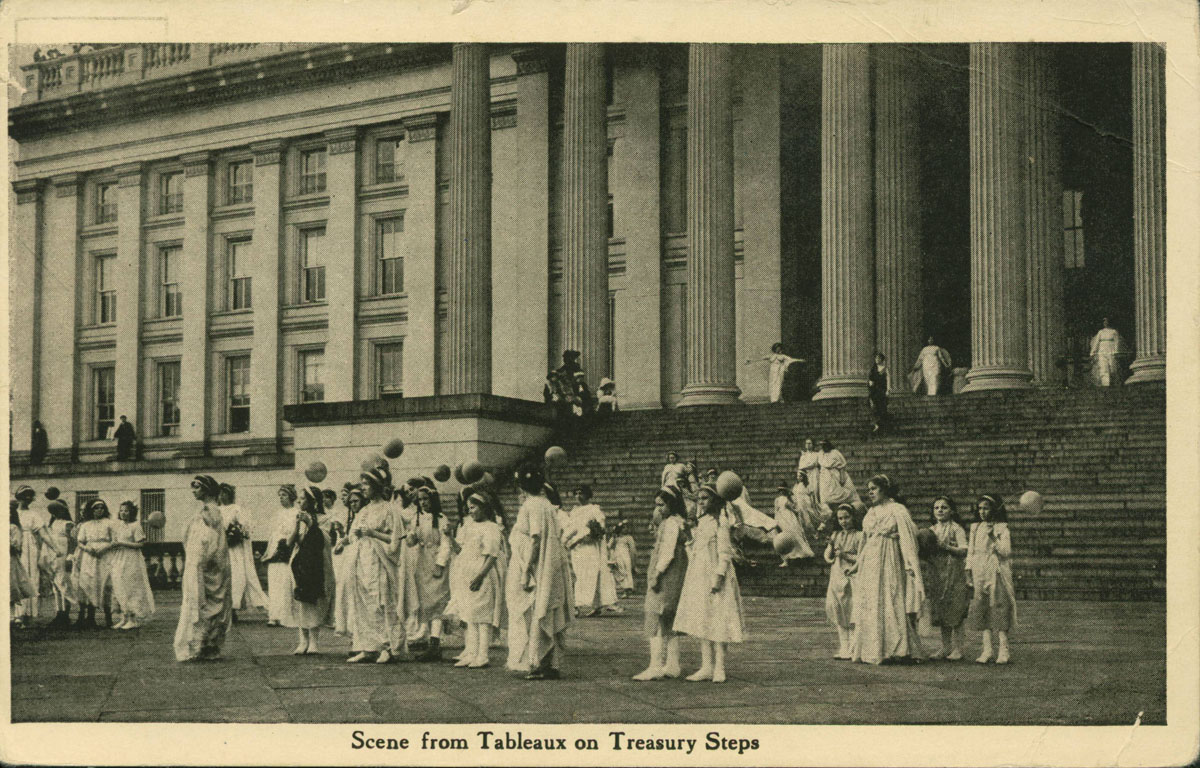

Leet and Ottenheimer Photos of the March 3, 1913 Suffrage Parade, Washington, DC

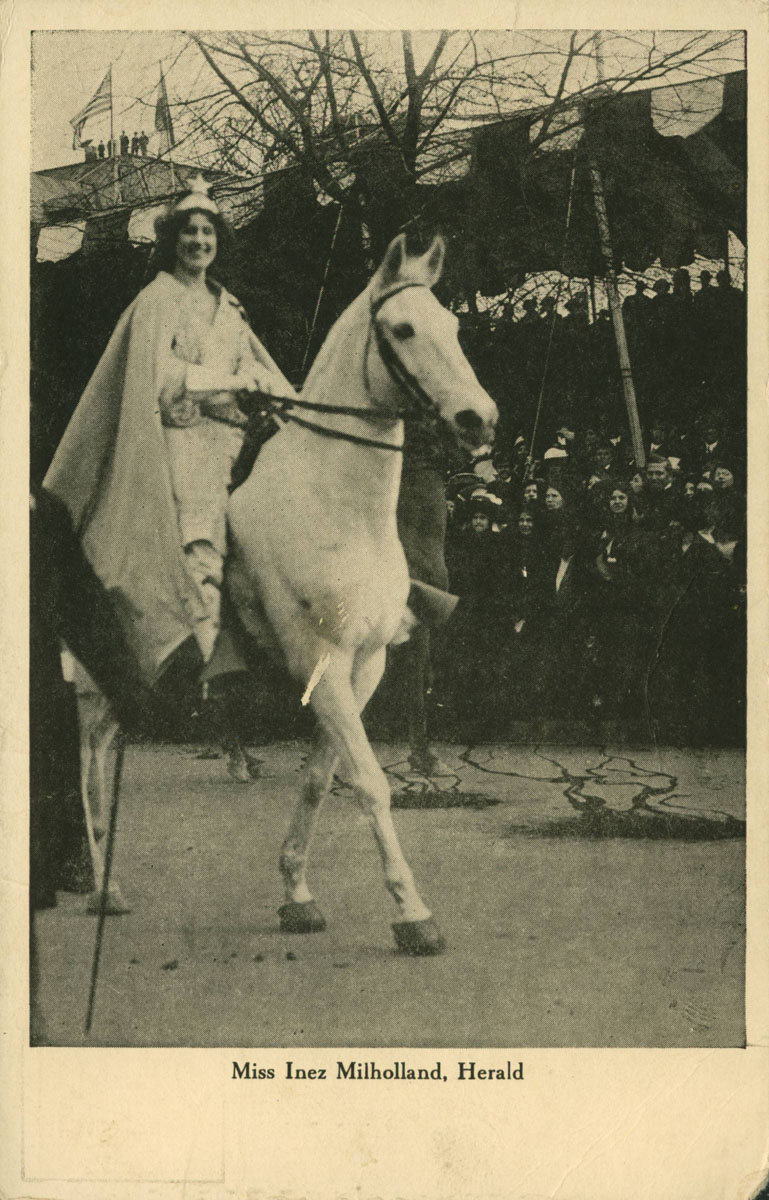

The rise of U.S. militancy found its roots in Alice Paul’s experiences in Great Britain. After Paul’s time with the Pankhursts and imprisonment in Great Britain, she returned to the United States with a new sense of militancy. In 1913, Paul, Lucy Burns and Crystal Eastman organized a parade the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Inez Milholland, known as “the most beautiful suffragette” [1] and thus capable of dispelling the idea that all suffragists were mannish harridans, clad in white robes and astride a white horse, led the parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. This parade was “the first national suffrage spectacle, its message trained solely upon a federal suffrage amendment."[2] Five thousand women participated in the parade as an estimated 100,000 watched (a crowd ballooned by the presidential inaugural to happen the next day.[3] The parade's power as an image event was not lost on the organizers. Just before the 1913 Washington, D.C. parade, suffragist Glenna Smith Tinnin wrote in an article for The Woman's Journal, "An idea that is driven home to the mind through the eye produces a more striking and lasting impression than any that goest [sic] through the ear." [4]

The crowd’s reaction (first verbally and then physically attacking the suffragists) and the police’s failure to respond catapulted woman suffrage into national attention. According to The New York Times, "for more than an hour confusion reigned. The police, the women say, did practically nothing, and finally soldiers and marines formed a voluntary escort to clear the way”; a police officer designated to guard the marchers was overheard shouting, "If my wife were where you are I'd break her head."[5] The following day, stories about the violence made the national headlines. Headlines declared “Washington Disgraced: Country Grossly Outraged” and “Hoodlums vs. Gentlewomen."[6] The cavalry from nearby Fort Meyer had to be called in by Secretary of War Stimson because the police could not, or would not, secure the parade route. The violence was so intense, congressional hearings would be held about it in March. Suffrage papers also described crowd reactions, with the Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News headline on March 4, 1913, declaring “Parade Struggles to Victory Despite Disgraceful Scenes.”

Not only did images of the parade appear in newspapers, but they also circulated in the form of postcards, the social media of that day. Postcards below were produced and sold by the Leet and Ottenheimer companies. In fact, the Leet images were introduced as evidence into the congressional hearings on the parade disruption and were sold at suffrage headquarters.[7]

This image is courtesy of Jackson's International Auctioneers and Appraisers, Waterloo, Iowa.

Endnotes

[1] “The Most Beautiful Suffragette,” Washington Post (March 2, 1913).

[2] Linda J. Lumsden, “Beauty and the Beasts: Significance of Press Coverage of the 1913 National Suffrage Parade,” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 77, no. 3 (Autumn 2000): 594.

[3] Sarah J. Moore, Journal of American Culture 20, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 89-103, 101. See also J. L. Borda, "The Woman Suffrage Parades of 1910-1913: Possibilities and Limitations of an Early Feminist Rhetorical Strategy," Western Journal of Communication 66, no. 1 (2002): 25-52.

[4] Glenna SmithTinnin, "Why the Pageant?" The Woman's Journal ( February 15, 1913): 60.

[5] "5,000 Women March, Beset by Crowds." The New York Times (March 4, 1913): 5.

[6] Moore, 101.

[7] Senate Subcommittee of the Sommittee on the District of Columbia, Suffrage Parade, 63rd Cong., Special Session, March 6-17, 1913, S. Res. 499, 33-8. |