Palczewski Suffrage Postcard Archive

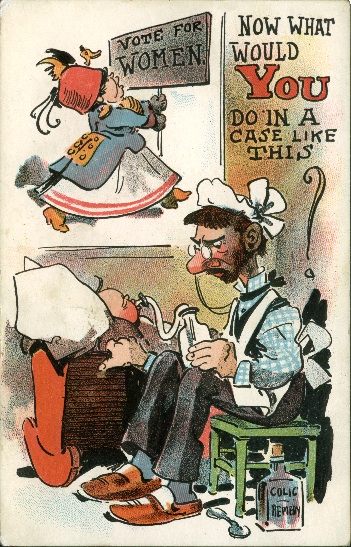

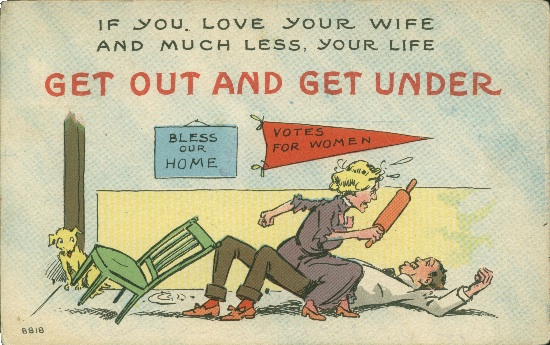

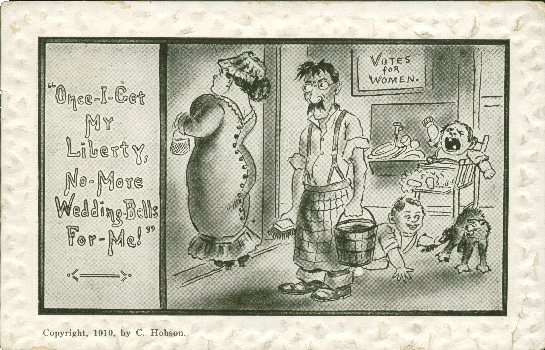

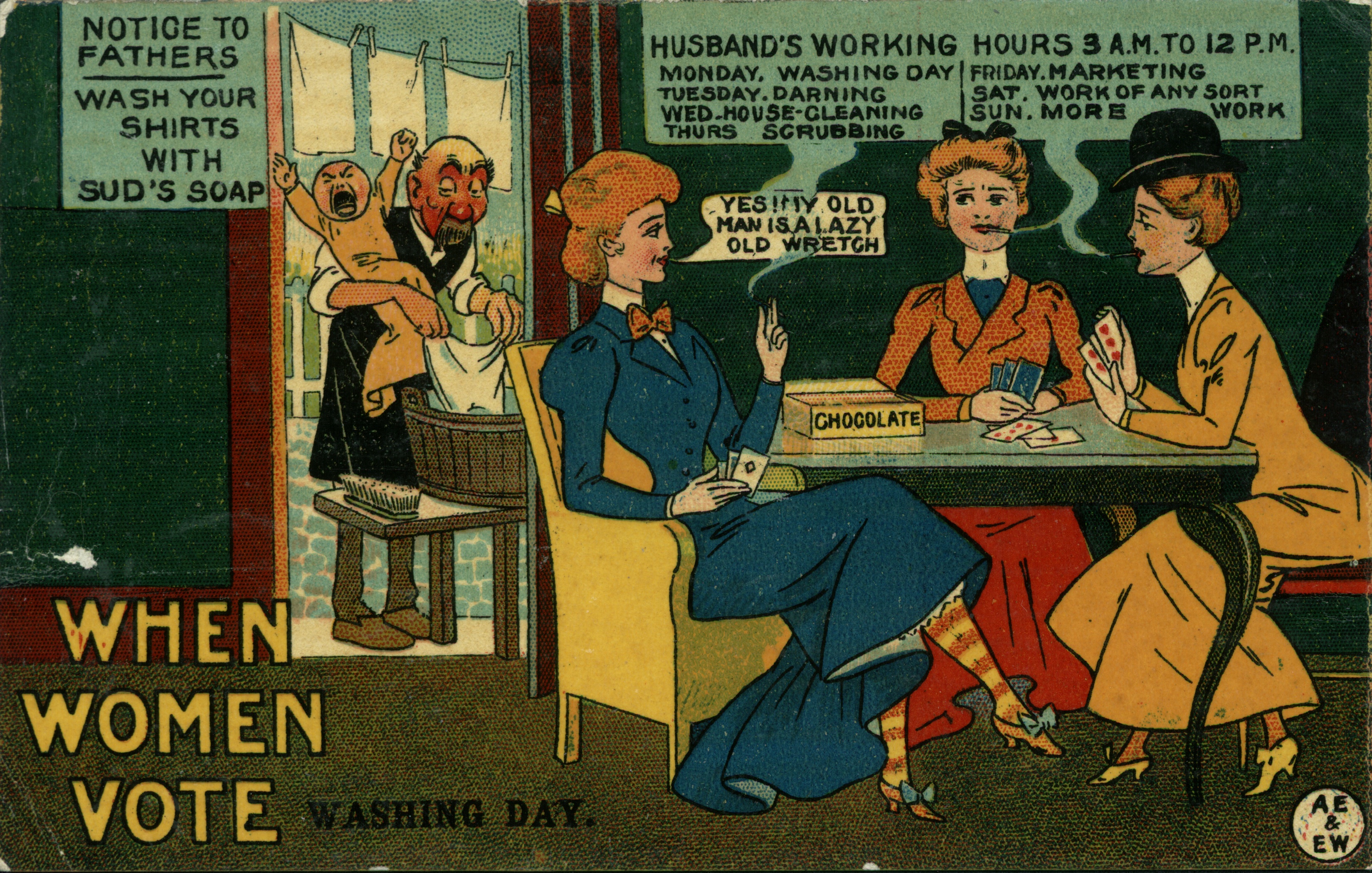

Feminization of Men (also see images from Dunston-Weiler)

During the Victorian era (1839-1901), clearly defined roles for men and women emerged. The roles persisted into the Edwardian era. Women were to be the “angel in the house,” while men were to face the vagaries of the public world of politics and commerce.

Suffrage advocates challenged the notion that women and the vote were unfit for each other, whether it be that women were unfit to vote, or that the vote would make women unfit to be women. These challenges to the prevailing images of womanhood did not go unanswered. In fact, not only did anti-suffrage images make clear how the vote would masculinize women, but they also presented an argument not present in the verbal discourse: that women’s vote would feminize men.

Understanding this dual move requires that one recognize the sharp division of spheres and duties that defined the time. At the turn of the century, “the ‘cult of domesticity’ and its attendant pictures of men and women . . . was a ‘major recurring image in Victorian literature, art and social commentary.’ This cult was firmly based in the concept of ‘separate spheres.’”[1] The public sphere, an “arena of business, politics, and the professions” was the world of men, while “the private sphere, the domain of love, the home, and family was the world of women.”[2] Women who violated the separation of spheres became “fallen women,”[3] or in the case of suffrage the “nagging wife” or the “embittered spinster.”[4] As Tickner explains, “the assumption that the ‘public’ woman was an unsexed harridan ran deep in contemporary thought.”[5]

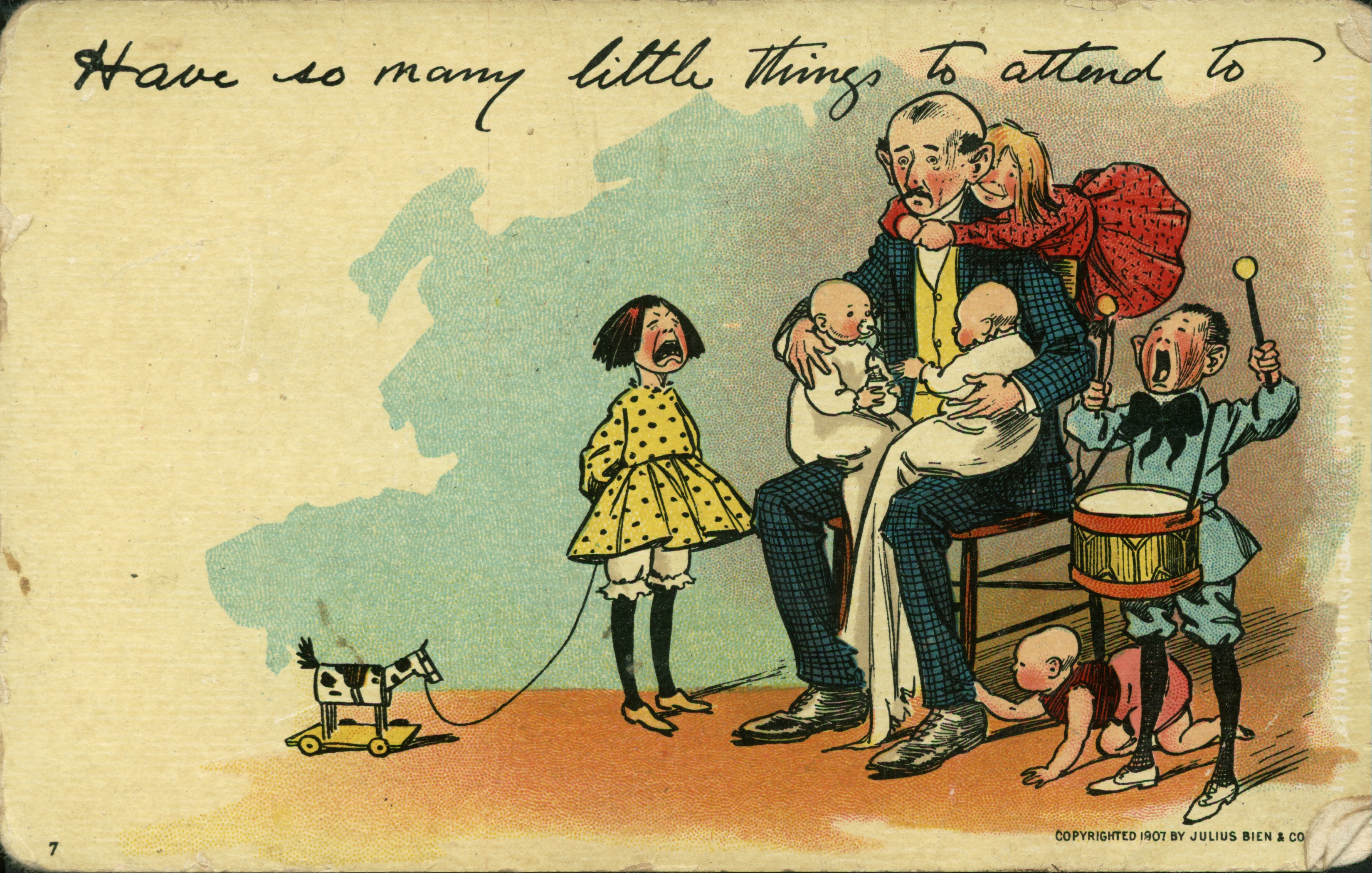

As Jorgensen-Earp notes in her analysis of Victorian images of women, “Dominant discourse and its images give structure to the concept of ‘woman.’”[6] Similarly, dominant discourse gives structure to the concept of man, in part by presenting what is not manly, by presenting men in locations typically populated by women. The corollary to the woman unsexed by the masculine vote was the man unsexed by the voting woman. Postcards repeatedly show “the bumbling man in the nursery, a staple of domestic comedy. Men were shown to be fumbling and incompetent in areas which really were ‘women’s work.’”[7] A number of British and U.S. postcards show men trying to do laundry, as the cat gets into the milk, and the children sit squawking. However, variations on this theme occurred, with some images showing men competently caring for infants, as in the Suffragette Madonna. Yet, even the competent male caregiver appealed to anti-suffrage sentiments, for then the image was of “the poor, tired husband home from his day’s labor only to find that he must mind the baby or do the dishes so that his wife may prepare a speech or attend a public meeting.”[9] He was the martyr to the suffrage cause.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes

[1] Cheryl Jorgensen-Earp, “The Lady, the Whore, and the Spinster: The Rhetorical Use of Victorian Images of Women,” Western Journal of Speech Communication 54, no. 1 (1990): 83.

[2] Ibid., 84.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Tickner, The Spectacle of Women, 164.

[5] Ibid., 151.

[6] Jorgensen-Earp, “The Lady, the Whore, and the Spinster,” 93

[7] Ibid., 88.

[8] Ibid., 89.

Palczewski suffrage postcard archive by Catherine Helen Palczewski. Please cite as follows:

Palczewski, Catherine H. Postcard Archive. University of Northern Iowa. Cedar Falls, IA.