Epilogue

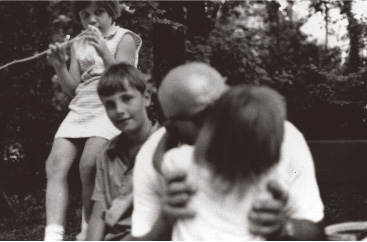

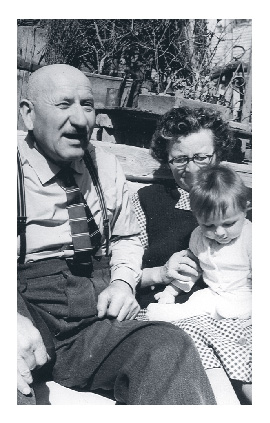

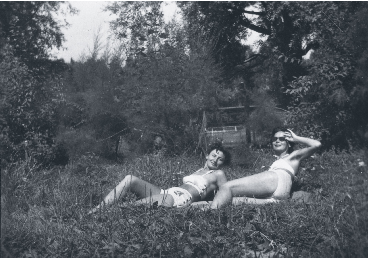

ASchildren in this photograph in 1939, Ari and Gyula couldn’t have imagined their lives would turn out this way. They loved each other, loved their family, and loved their life on the farm. Yet, in the next two decades their own country would plunge them into a horrible war; exterminate their Jewish neighbors; arrest, torture, and imprison Gyula and his father; push the family off of their land; and tear sister and brother apart. What happens when your own country does this to you?

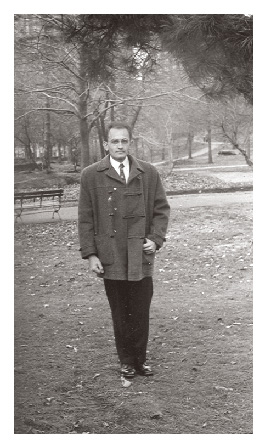

GYULAescaped to Vienna. Months later he gained passage on the General Le Roy Eltinge, a U.S. Navy transport ship, to the United States as a refugee.

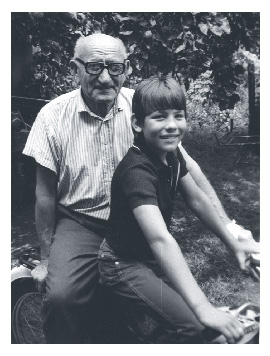

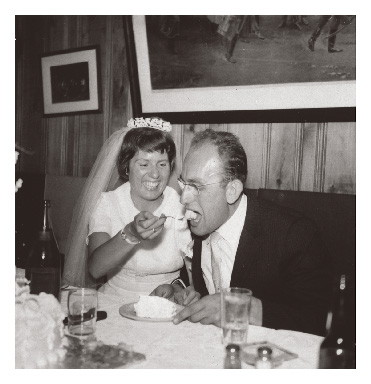

He continued his studies in agronomy at Rutgers in New Jersey and married a Swiss kindergarten teacher named Edith Haüsermann in 1959. Later on, Gyula went to Harvard to study landscape architecture and became a professor of landscape planning in Amherst, Massachusetts.

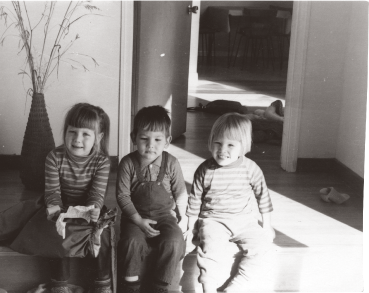

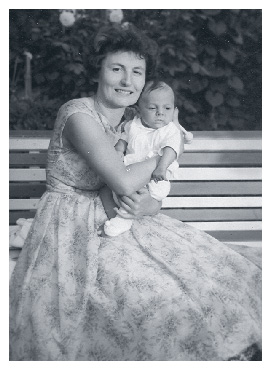

Gyula and Edith had three children: Anita, Adrian, and Bettina. I am the “youngest,” a twin, born five minutes after my brother in 1965.

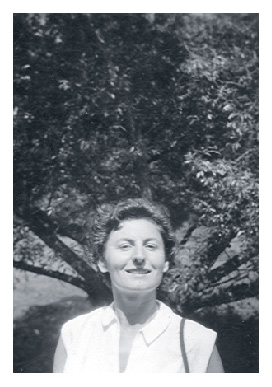

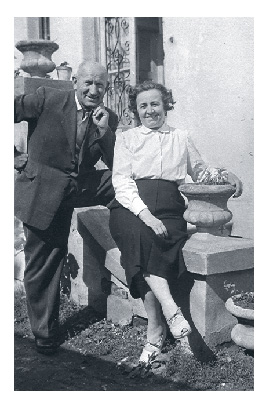

ARI,though she remained in Hungary, moved farther away from the family’s roots by marrying László Hévizi, a Budapest-trained lawyer and chess champion.

Pista and Gizi could not relate to László’s big city ways or formal education. László knew nothing about farm life.

According to family lore, he criticized Gizi’s salad dressing (it may have just been a misunderstanding), making his relationship with Ari’s parents grow so strained that he rarely went with Ari to visit Keszthely.

Ari and László had a son, László Hévizi, Jr., known as Laci.

They lived a modest life in a small apartment on Hungária Körút, one of the commercial thoroughfares encircling Budapest. They learned to survive the post-’56 communist system.

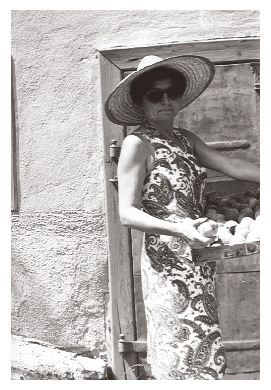

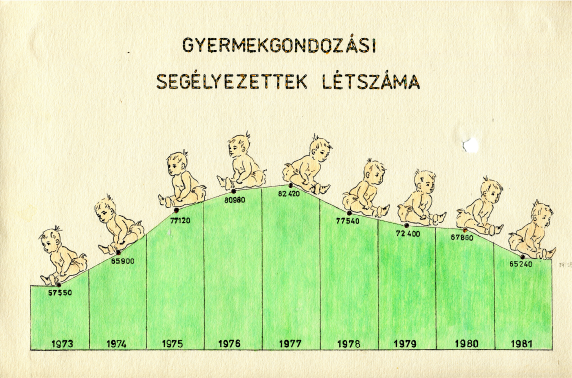

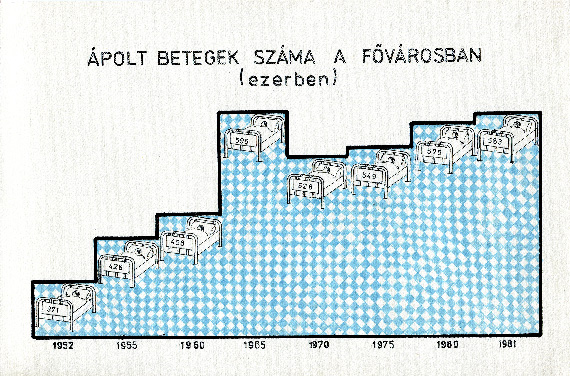

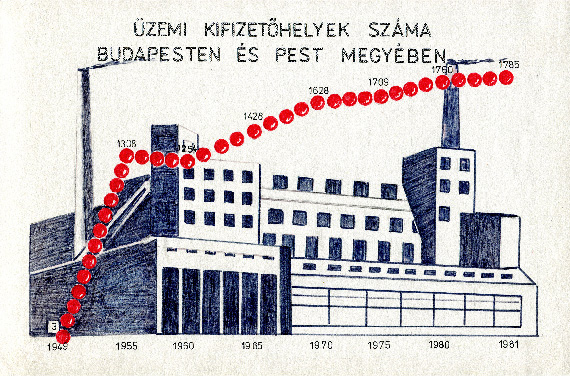

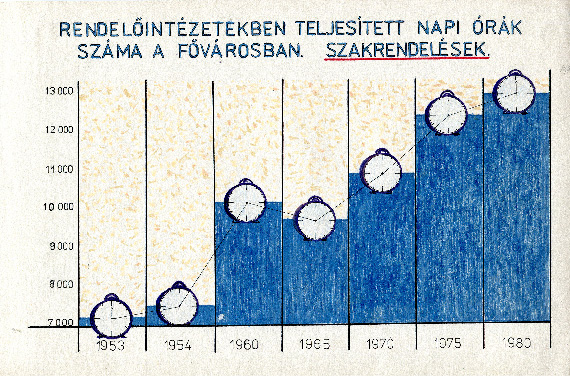

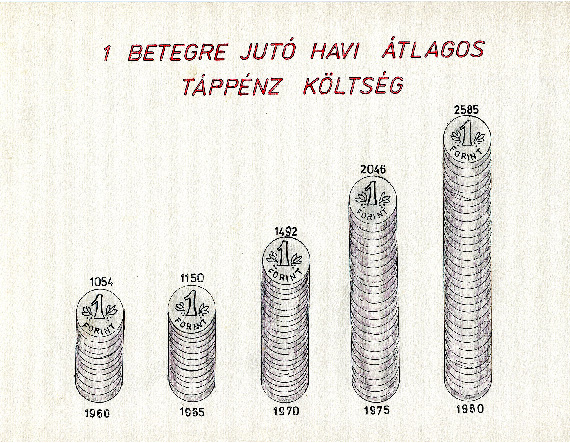

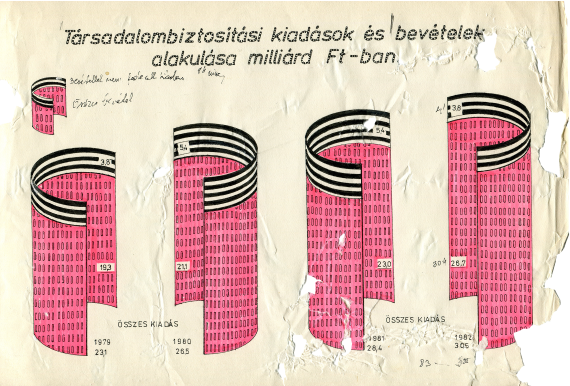

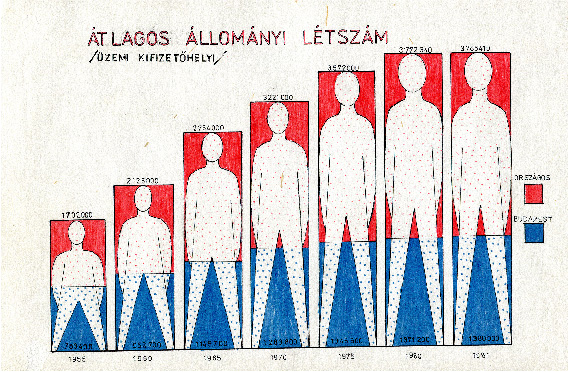

And after ten years working as a statistician, Ari finally became an artist! In 1966, the state health insurance company needed someone to promote the progress of universal health care, and it turned out that she excelled at data visualization.

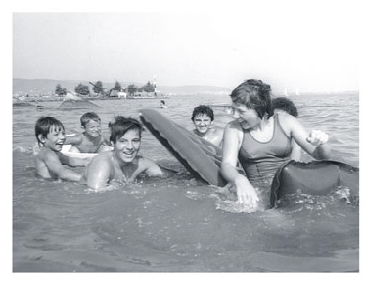

Ari and young Laci visited Lake Balaton as often as possible as a reprieve from the busy city. One enduring luxury in communist Hungary was an abundance of time.

PISTAwas arrested by Soviet-backed authorities a year after Gyula’s escape in 1956. He was sentenced to six months hard labor in Tököl, south of Budapest—punished, it became apparent, for his son’s participation in the revolution and subsequent escape from Hungary.

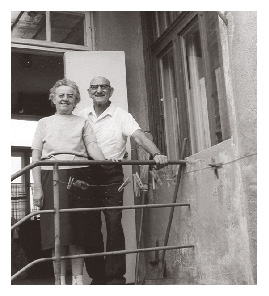

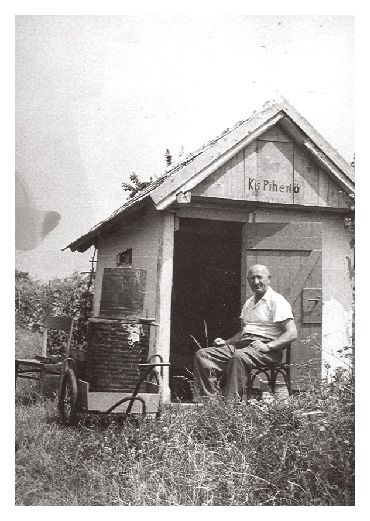

Pista survived the camp and came home to his job as a postal worker. He maintained two tiny vineyard plots, one in Marcali, the other near Keszthely. He made excellent wine, which he privately sold in his backyard.

GIZIstruggled to acclimate to the new system. She lost her son to America, her husband to forced labor, and her daughter to Budapest.

In the 1960s, she had thrombosis (a clot in her vein) and was not quite the same anymore, becoming ever more dependent on Pista and deteriorating mentally and physically. For Gizi, adapting to life off the farm was next to impossible.