The Caves of Marble Mountain |

||

Wayne I. Anderson |

||

|

||

Marble Mountain, in the background, is composed of gray limestones of the Minturn Formation, the deposits of an ancient sea. Hiker, in foreground, provides scale. |

||

What would you answer if asked: “What type of rock is found on Marble Mountain?” Marble would seem like a logical response, but it would be incorrect. The prominent, light-gray rock exposures along the east side of Marble Mountain are limestone. Limestone is a sedimentary rock. Marble, a metamorphic rock, forms by recrystallization of limestone under moderate increases in temperature and pressure. Fossil invertebrates such as crinoids (sea lilies), brachiopods (shell fish), and gastropods (snails) help document a marine origin for the limestones of Marble Mountain. Algal structures and limy remains of amoeba-like foraminifera also occur in the limestones. Assigned to the Minturn Formation, these limestone deposits formed in an ancient inland sea some 300 million years ago. |

|

|

||

Fossils of a variety of marine invertebrates are common in the limestones of the Minturn Formation and can be found along the slopes of Marble Mountain and elsewhere in the Sangres. Fossils illustrated here include (upper row): snail, brachiopod, and stem segments of a crinoid (sea lily); (lower row): two views of a common brachiopod and a crinoid in growth position on the sea floor. Width of a typical fossil is 1.0 to 1.5 inches. |

||

The limestone exposures are clearly visible along the east flank of the Sangres between Music Pass and South Colony creeks. At least 11 caves occur within the limestone bedrock of the area. Of these caves, Marble Cave and White Marble Halls Cave are best known. According to Michael O’Hanlon, the caves of Marble Mountain have produced more lore and tall tales than any other localities in the Colorado Sangres. Stories of hidden Conquistador gold and skeletons in chains are associated with the caves of Marble Mountain. However, as Dodds (1992) points out, the skeletal remains were reported by Elisha P. Horn in 1869 in an old fort some distance below Marble Cave. An account from 1929, described by Dodds (1992), states that an old log-and-stone fort was discovered some thousand feet below the side of Marble Mountain. I have visited both Marble Cave (Spanish Cave) and White Marble Halls Cave and find it difficult to believe that anyone would occupy these caves, other than for very short periods of time. The caves require crawling for access and the entrances to both are usually filled with ice and snow until mid-or-late summer. Legendary Marble Cave extends several thousand feet, but only the first thirty feet are safe for amateurs to explore. Lloyd Parris in According to Dobbs (1992), Spanish legends tell of the Conquistadors entering Spanish Cave from an opening on the west flank of the Sangres and working rich mines. This appears to be more of a myth than a factual account, however. Study of a geologic map or cross section reveals that limestone is exposed on both the east and west flanks of Marble Mountain. See diagram below. Limestone is the rock material in which caves form. However, most of the Sangre de Cristo Range, between Marble Mountain and the San Luis Valley, is composed of resistant Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks, not the kind of rock materials in which caves form. |

|

|

||

Limestones of the Minturn Formation underlie Marble Mountain and are the host rock for the numerous caves of the area. The Minturn Formation is in fault contact with the Sangre de Cristo Formation on the east and the Precambrian igneous and metamorphic bedrock to the west. Based on information in Lindsey et al., 1986. |

||

Spanish Cave and the other caves of the area formed where slightly-acidic groundwater slowly dissolved limestone bedrock along joints, fractures, and bedding planes. This dissolution produced tube-like passages that rarely exceed 15 feet in diameter. Only a few large rooms are known in the caves of the Marble Mountain area. However, deep, narrow, canyon-like features have been discovered, and some of these so-called canyons are at least 100 feet deep. Parris reports that Spanish Cave, with over 3,500 feet of passageways and approximately 700 feet of relief, is probably one of the deepest caves in the nation. It contains many unexplored areas. Exploration of the inner reaches of Spanish Cave should be left to experienced spelunkers. Rope work is required and investigators must be able to “chimney” up or down vertical chasms for extended periods of time. According to Parris, Spanish Cave is the longest and most dangerous cave on Marble Mountain. |

|

|

||||

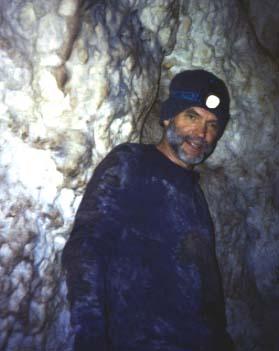

A thoroughly-modern "Cave Man" crouches in the entrance of Spanish Cave, 7-31-2006. Note snow in the cave opening. |

||||

Parris notes that the floor of Spanish Cave is covered with broken travertine deposits in places and this produces a sound like broken crockery when walked on. Stalagmites and stalactites are rarely seen, but flowstone and dripstone deposits of travertine are common. The cave “breaths” (expires and inspires air from the outside) several times a day. At times, the air movements are strong enough to extinguish a carbide lamp. White Marble Halls Cave was initially called Yeoman’s Cave in honor of its discoverer, J. H. Yeoman. Yeoman found the cave on September 16, 1880. On September 6, 2000, nearly 120 years later, Mike O’Hanlon and I came to take a look. Mike had visited this cave several times previously. He led the way, unrolling 418 feet of cord to mark our exit to the outside in case we got disoriented. I found the presence of the cord and the companionship of someone who knew the cave to be reassuring. I had crawled in tight caves before, but it was over 25 years ago. A Denver newspaper article in 1888 referred to Yeoman’s Cave as “Rival of Mammoth Cave.” Mr. Yeoman’s description of the cave, included in the article, provided the following details: entrance to the cave is by a crevice in the rock, extending some 400 feet; upon entering one must crawl a distance of 25 feet; then, the investigator can walk in a stooping posture for 25 feet; next, a narrow passage is encountered through which only a person of small stature can pass; and finally a low passage is reached through which one gains entry to the King’s Chamber. Yeoman’s details seem fairly accurate, although at least one correction is in order. I can personally verify that a person of average to above-average stature can reach the King’s Chamber after an appropriate amount of stooping, crawling, scooting, and squirming. However, persons with a tendency toward claustrophobia should think twice before considering entry into White Marble Halls Cave. You will need to squeeze through a couple of very tight passages! |

|

|

||

Map of White Marble Halls Cave. M.O. and W. A. represent the outlines of cave explorers, crawling through the narrow passages of the cave. Adapted from Parris, 1973, |

||

Parris describes entry into White Marble Halls Cave as being “over 400 feet long, passing through damp chilling crawlways over pits and breakdowns, and through tight keyholes which are generally covered with bat guano.” Mike and I didn’t encounter bat guano, but the rest of the description by Parris rings true. We observed a small amount of mammal scat in the entry passage, probably the product of a marmot. The only other evidences of life we saw were some abandoned devices, likely used by cave explorers to wind and unwind rope or cord. Mr. Yeoman described the King’s Chamber as having “walls as white as snow” and a height of 175 feet. According to Parris, later measurements by spelunkers place the chamber’s height at about 30 feet and its width at 20 feet. The “walls” observed by Yeoman remain quite striking, and the “white” travertine deposits that coat them suggest that flowstone and dripstone are still being deposited in the cave. A low passage leads into the Queen’s Chamber, which although smaller than the King’s Chamber is also characterized by beautiful white walls. Parris describes the Queen’s Chamber as a circular, dome room, 10 feet wide and 20 feet high. We noted attractive travertine deposits of flowstone and dripstone in the Queen’s Chamber, and it, like the King’s Chamber, appears to be part of a living cave system with ongoing deposition of calcium carbonate. Parris (1973) in For information on planning a hike to the caves of Marble Mountain, consult O’Hanlon’s excellent resource, |

|

|

||||

Mike O’Hanlon in the Queen’s Chamber of White Marble Halls Cave in September of 2000. Mike wrote The Colorado Sangre de Cristo: A Complete Trail Guide. |

||||

I will always remember my trip to Marble Mountain and White Marble Halls Cave with Michael in September of 2000. It is an experience that I treasure and one that I will never forget. Michael died in July of 2002 as a result of a fall while descending Mt. Adams in the Colorado Sangres that he knew so well and loved so much. |

|

References Dodds, Joanne W. 1994. Lindsey, David A., P. A. M. Andriessen, and Bruce R. Wardlaw. 1986. "Heating, Cooling, and Uplift during Tertiary Time, Northern Sangre de Cristo Range, Colorado." Macan, Randy. 2006. Personal communication. O'Hanlon, Michael. 1999. Parris, Loyd E. 1973. |

|

|

|

|

||||